Imagine running payroll, closing the books, and drafting board-ready reports – for a 1,000-employee company – with just a handful of accountants. Thanks to AI, this is no longer a fantasy. It’s the next leap in a centuries-long evolution. From Renaissance merchants tracking ledgers to cloud fintechs embedding finance into every app we use. Each wave of technology has made finance faster, but has still required humans to stitch it all together.

We are now in the AI era, where just about every sector is making the most of what AI has to offer. The accounting sector is not left out, and this time, its evolution is a different kind. Rather than automating a single layer, AI learns across all layers, creating a level of thoroughness where a mid-sized company can now imagine running its entire accounting sector with just a few AI-literate professionals.

In more in-depth detail, we are going to cover the stages of this accounting evolution and take it one step further — illustrate how the accounting sector can make the most of it to cut down workload and increase efficiency.

The Evolution of the Accounting Department

Over the past decade, the accounting sector has broken out of its traditional, back-office confines. Once dominated by bookkeeping, compliance, and budget policing, it now sits at the center of corporate strategy. Accountants routinely partner with product leaders on pricing decisions, guide mergers and acquisitions with scenario modelling, and shape company culture through policies on compensation and ESG investments.

When Adobe pivoted from boxed software to a cloud-subscription model, for example, it took the former Chief Financial Officer, Mark Garrett, and CEO, Shantanu Narayen, to quantify the short-term revenue dip, model retention curves, and demonstrate the long-term lift to free cash flow. These insights gave the board the confidence to proceed. Similar stories are playing out across industries: Gartner has noted that financial applications are now viewed by more than a third of enterprises as critical components of their overall digital strategy, underlining how deeply finance is woven into technological decision-making.

The Influence of Artificial Intelligence

At the same time, the nature of the work in accounting is being reshaped by artificial intelligence, as the operational core is being automated away. A reflection of the pattern, Bill Gates said, when he quoted that “The first rule of any technology used in a business is that automation applied to an efficient operation will magnify the efficiency. The second is that automation applied to an inefficient operation will magnify the inefficiency.”

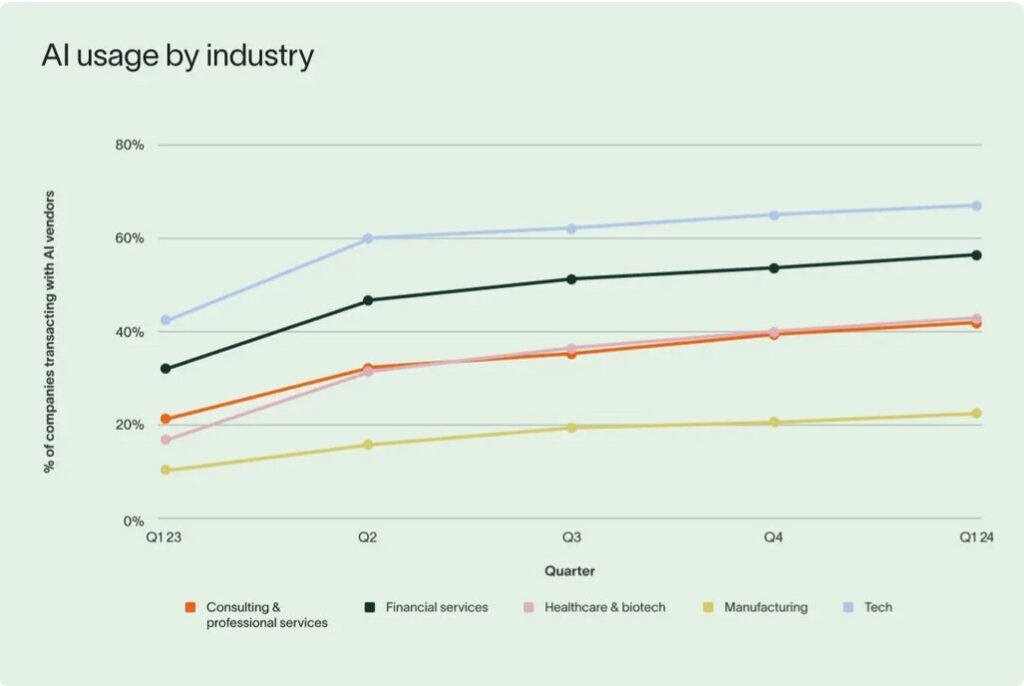

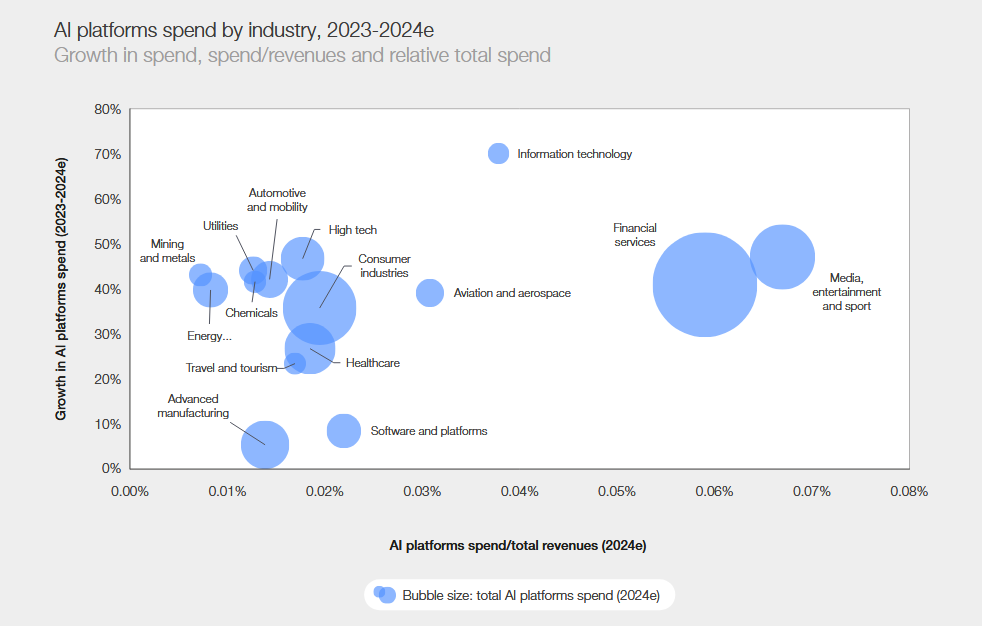

The scale of that automation is easiest to see in spending patterns, as shown in this image.

Accenture Research. Data from Accenture’s G2000 list.

Financial services stand out in two respects. First, only media and information technology firms are projected to spend a larger share of revenue on AI; second, the sector’s spending is growing faster than IT’s, which shows an aggressive push to scale early pilots. This isn’t about ‘if’ anymore—it’s about how fast you move. Companies that wait risk getting left behind.

These two developments— a broader, more strategic mandate for accountants and a rapid automation of their traditional workload—now overlap. As intelligent platforms assume responsibility for routine accounting, reconciliation, and even first-pass variance commentary, headcount dedicated to those activities can be reduced dramatically.

What remains is higher-order work: orchestrating the data architecture, validating model outputs, interpreting insights for the business, and designing controls that keep algorithms both accurate and compliant. In this environment, you don’t need a dozen accountants to close the books. You need two smart professionals who understand the tools that do it faster—and better.

The AI-Powered Accounting Function

Artificial intelligence is no longer an experimental add-on to finance operations; it is fast becoming the operating system for the entire function. Because most accounting workflows depend on large volumes of structured data and repeatable language-based tasks — reconciliations, policy checks, variance commentary, customer correspondence — AI can automate or augment a surprisingly large share of day-to-day work.

What emerges is a two-layer model: a fabric of intelligent services that executes routine processes at scale and a very small human team that sets policy, manages risk, and interprets the insights the machines produce.

How AI Performs the Work

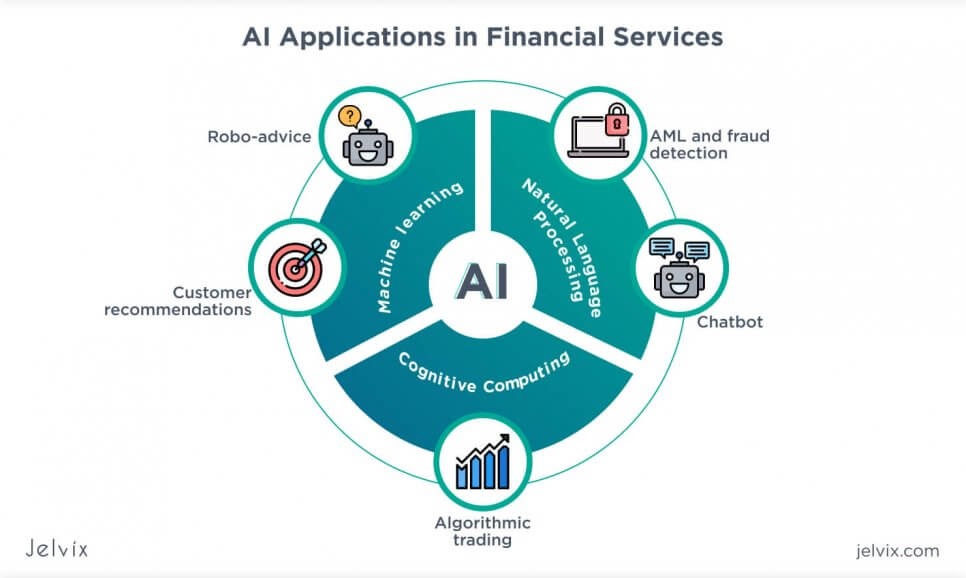

At its core, AI functions in three aspects for finance:

Perception and extraction: Computer-vision and natural-language models “see” invoices, contracts, and e-mails, extract the relevant fields, and pass clean, structured data directly into the general ledger or forecasting engine.

Reasoning and prediction: Machine-learning models spot anomalies in journal entries, forecast cash positions, or score credit risk by continuously learning from historical and real-time data.

Interaction and advice: Generative AI systems turn raw numbers into plain-language narratives—drafting board memos, answering vendor queries, or guiding customer-service agents through complicated policy questions.

In every case, the pattern is the same: AI handles the routine cognitive work—reading, matching, deciding—so that scarce human talent can concentrate on judgment-heavy activities such as policy design, scenario planning, and stakeholder communication.

How the Big 4 Have Adopted AI

The Big Four—Deloitte, EY, PwC, and KPMG—have long set the pace in the accounting industry, shaping standards and adopting new technologies ahead of the curve. Following an unsurprising trend, they have their hands in the proverbial AI pie and are once again steering the accounting profession.

We start with Deloitte and EY and their agentic AI—autonomous agents that analyze, decide, and act with little oversight—to handle finance and tax tasks. More specifically, Deloitte’s Zora AI supports financial analysis, expense management, and forecasting, with expected savings of 25% in costs and a 40% productivity boost. EY’s AI Agentic Platform equips 80,000 tax staff with 150 agents to process 3 million deliverables and 30 million tax workflows annually.

PwC and KPMG are building custom AI agents for auditing, software development, and global service delivery, partnering with Microsoft, Salesforce, and Oracle, while KPMG develops “digital teammates” to improve service quality and efficiency.

What This Means for an In-House Accounting Team

When AI takes over the day-to-day grind, the function and value of accountants shift dramatically—especially when there are only two of them running the whole function. Responsibilities change from running transactions to orchestrating technology, stewarding ethics, and translating machine insight into business action. This overhaul takes place with four broad changes:

1. A pivot from “doing” to “directing.”

AI platforms now post journals, chase invoices, and draft first-pass variance explanations; accountants, therefore, spend less time keying numbers and more time overseeing automation. This demands fluency in how models pull, clean, and classify data.

A controller who once reconciled cash accounts manually must now verify that the reconciliation algorithm is drawing from the right feeds, handling edge cases correctly, and surfacing true anomalies rather than noise. In practice, the job feels less like accounting and more like systems engineering blended with financial judgment.

2. Deeper engagement in strategy and change.

Like Clara Durodie points out, the true value of AI in finance lies not just in efficiency gains, but in its ability to uncover deep, previously hidden insights from vast datasets, leading to superior decision-making in complex environments.

Freed from routine close cycles, a lean accounting team can sit beside product and sales teams to frame pricing experiments, evaluate new markets, or model alternative capital structures. That advisory role requires data-driven decision-making, the ability to shape narratives around AI-generated forecasts, and critically change management skills. When AI alters a long-standing workflow, someone must reassure stakeholders, document the control environment, and coach colleagues through the transition.

3. A continuous-learning mandate.

Because machine-learning techniques evolve quickly, the accounting sector of a company becomes a perpetual classroom, and the accountants, perpetual students. Now, these students have to adapt to and get a working grasp of AI concepts—feature engineering, drift detection, and prompt design—enough to challenge vendors and interpret model outputs.

They also need cross-functional literacy: understanding how treasury data flows into the data lake, how procurement approves new SaaS spend, or how HR measures engagement, because AI solutions now span those areas.

4. Ethical and communicative leadership.

Automated decisions—credit limits, fraud flags, expense rejections—carry real consequences for customers and employees. Accountants must embed AI-ethics checkpoints that guard against bias, ensure transparency, and satisfy auditors. They must then communicate those guardrails in plain language to boards, regulators, and staff. Doing so calls for clear storytelling, project-management discipline during roll-outs, and a willingness to own outcomes when the algorithm gets it wrong.

Taken together, these shifts redefine the ideal accountant. Excel wizardry and debits-equal-credits remain table stakes, but the differentiators are now AI stewardship, strategic foresight, ethical governance, and the agility to learn. An in-house team of a few people can indeed run an accounting team for a 1000-employee company—but only if they evolve into this new breed of adaptive, AI-literate experts.

Implementation Roadmap

A practical guide to shrinking a mid-sized company’s accounting department to two AI-enabled experts.

Phase 1 – Align on Vision and Risk Appetite

Begin with a board-level conversation that crystallises why you want an ultra-lean accounting model and how much automation risk the organisation is willing to shoulder. Document success metrics—cycle-time targets, cost savings, control thresholds—and secure explicit support from the CEO, CIO, and audit chair. This alignment prevents mid-project scope creep and ensures every later decision (tool choice, staffing, governance) traces back to a single, shared objective.

Phase 2 – Baseline & Process Audit

Map every accounting activity—from invoice capture to board-pack publication—and tag three attributes: manual effort, system touch-points, and control criticality. The goal is to pinpoint high-volume, rules-based tasks that machines can absorb quickly (e.g., three-way PO matching) versus judgment-heavy steps that will remain with the few accountants. Capture baseline KPIs (close timetable, cost per invoice, error rates) so the impact of automation can later be proved, not presumed.

Phase 3 – Data Foundation & Platform Selection

Once you know where the problems are, focus on the system you’ll build. AI only works well if the data it sees is clean and clearly labeled, so start by setting up one reliable source for all your financial data—usually a cloud-based ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning system) that can easily connect to other apps. Then add top-quality AI tools (for example, software that automates payables, spots unusual transactions, or writes plain-English reports) that plug straight into the ERP instead of relying on fragile spreadsheet links. When you compare vendors, judge each one on three things:

Model transparency: Can you inspect how predictions are made?

Control hooks: Can exceptions be routed, approved, and logged for audit?

Scalability: Will licensing or computing costs still make sense at 10× transaction volume?

Phase 4 – Pilot & Workflow Redesign

Choose one high-volume process—say, accounts payable—and run it end-to-end on the new stack. Keep humans in the loop but in a supervisory role: they review AI-flagged anomalies, not every invoice. Measure cycle time, error reduction, and user satisfaction against the baseline. Use findings to redesign SOPs, shifting responsibility from “who keys the entry” to “who validates the model.” Train non-finance stakeholders (procurement, department heads) on the new approval UX so that friction is surfaced early.

Phase 5 – Scale, Controls, and Change Management

Once the first AI pilot meets its goals, start applying the same approach to nearby tasks—such as expense checks, bank reconciliations, and the month-end close—one at a time. For each task, you first set up the new system, test it, run it alongside the old method, and then switch over completely; the whole cycle usually takes two to four weeks.

As you expand, build in three safeguards: drift monitoring that alerts you if the model’s accuracy slips, bias tests that make sure credit limits and fraud flags stay fair, and tamper-proof audit logs that record every data source and AI decision for easy tracing. Finally, hold casual “lunch-and-learn” sessions every month so employees can see how the new system works—open conversations prevent the AI from feeling like a mysterious black box.

Phase 6 – Continuous Optimisation & Talent Evolution

Automation is not a set-and-forget exercise. Establish a quarterly “model health check” where the few accountants, IT, and internal audit review performance metrics, false-positive rates, and new regulatory guidance. As AI frees capacity, redirect that time to value-added analytics—pricing elasticity studies, cash-conversion-cycle diagnostics, ESG-linked KPI modelling. Simultaneously invest in the duo’s skills: prompt engineering, ethical-AI governance, and data storytelling. Their relevance—and the system’s credibility—depend on relentless upskilling.

Putting It All Together

Executed sequentially, these phases move the organisation from fragmented manual workflows to an integrated, AI-first accounting engine in roughly 12 months. The few accountants who have overseen the revolution become architects and guardians of that engine, validating data, refining models, and translating insights for leadership.

The endpoint of this revolution is an accounting system that closes books in hours, flags risk in real time, and costs a fraction of its traditional footprint, without compromising on control or strategic influence.

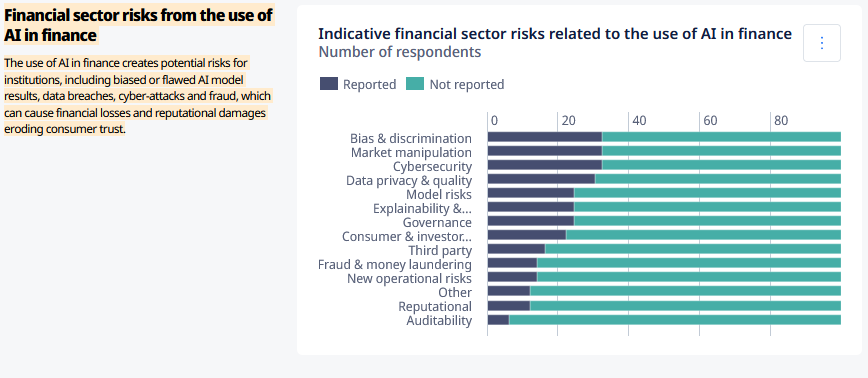

Risks and Challenges of a Two-Person, AI-Driven Accounting Team

Implementing an almost fully automated accounting system unlocks speed and cost advantages, but it also introduces new risk factors. Four hazards, in particular, deserve sustained attention.

1. Over-reliance on automation.

AI systems can misclassify transactions, propagate faulty rules, or hallucinate narrative explanations. When only few people supervise thousands of automated postings, a single undetected error can ripple through financial statements, tax filings, and investor reports.

The safeguard is layered human oversight: exception dashboards that surface anomalies in real time, mandatory spot-checks of material journal entries, and clear kill-switch authority that communicates to the accountants to pause a model that is behaving unexpectedly.

2. Data-integrity threats.

Machine-learning outputs are only as reliable as the data that feeds them. Ingesting duplicate invoices, outdated FX rates, or mis-mapped chart-of-accounts codes will cause even the most sophisticated model to deliver garbage results at machine scale. A robust master-data-management framework—complete with field-level validations, version control, and automated reconciliation to source systems—becomes non-negotiable. Periodic data-quality audits and reconciliations to bank and sub-ledger balances help catch blind spots that AI may miss.

3. Heightened regulatory scrutiny.

Regulators and auditors are growing wary of “black-box” financial systems. A lean team must therefore demonstrate that every algorithmic decision is explainable, traceable, and compliant with accounting standards. Embedding audit-ready logs—who changed a model parameter, why a transaction was auto-approved, how drift was detected—creates the transparency external parties demand. Annual third-party model-risk reviews and SOC-1/SOC-2 reports can further reassure boards and regulators that controls have kept pace with automation.

4. Organisational change fatigue.

Shifting from manual processing to AI-centric workflows can unsettle employees whose roles, metrics, and even identities were tied to hands-on accounting tasks. If unmanaged, that anxiety can translate into resistance, reduced data quality, and talent attrition. The antidote is proactive change management: early communication of the “why,” hands-on training for new tools, and a clear path for redeploying people toward analytical or client-facing work. Celebrating early wins, such as a 90-percent reduction in close-cycle time, helps employees see the upside rather than the threat.

Mitigation in Practice

A lean accounting team survives these risks by weaving governance into its daily rhythm: automated controls that alert on anomalies, quarterly model-health reviews with IT and internal audit, and a standing escalation protocol that routes unresolved exceptions to the CFO or audit committee. In effect, good governance replaces sheer headcount.

Conclusion

Running a 1000-employee corporation with just a few accountants once sounded like science fiction. Today, it is simply the logical consequence of three converging forces: inexpensive cloud infrastructure, mature AI models that excel at language and data-centric tasks, and a growing body of governance practices that make automation auditable and trustworthy.

The opportunity is therefore not just to cut costs, but to recast accounting as a high-leverage cockpit for real-time decision-making—a function that sees risk sooner, models scenarios faster, and engages the board with clearer, more forward-looking narratives. Companies that embrace this shift will discover that lean does not mean fragile; in an AI-first world, lean means focused, agile, and relentlessly value-creating.

About the Author:

Oran Yehiel is a U.S.-based CFO and founder of Startup Geek, supporting tech startups with strategic finance, growth execution, and capital raising. He’s helped founders raise over $250M and prepare for IPO and M&A.