You’ve just closed your seed round. Your product is gaining traction. And your brilliant CTO just convinced you that hiring a development team in Bangalore will stretch your runway by 18 months. So you do it. You set up an Indian subsidiary, move five engineers onto the payroll, and get back to building.

What you don’t realize is that you’ve just triggered something called transfer pricing—and the decisions you make in the next few weeks could cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars down the line.

Out of the goodness of our hearts, we will be breaking down the concept of transfer pricing and potentially save you precious money in penalties. We will cover what transfer pricing is, the types, and when you need to start taking it seriously. Elaborate enough, right? Well, consider it a Christmas miracle.

Let’s get to it!

What is Transfer Pricing?

Transfer pricing is the pricing of transactions between related entities, such as a parent company and its subsidiaries, or between two subsidiaries of the same parent, operating in different tax jurisdictions.

In simpler terms, when two companies you own do business with each other across borders, the prices you charge for goods, services, intellectual property, or loans between them are your transfer pricing.

Remember that Indian subsidiary you just set up? Well, your US parent company and your Indian subsidiary are going to transact with each other. Your Indian team will build features, fix bugs, and ship code. Your US entity will pay them for this work.

But here’s the question that tax authorities in both countries are now asking: How much should your US company pay your Indian subsidiary for those engineering services?

Arm Length’s Principle

The year is 1928, and the US IRS just made a provision that was significantly expanded in 1968. It began with Section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code, and this provision gave the IRS authority to adjust income and deductions between related parties to prevent tax evasion and ensure income is clearly reflected. The law introduced what became known as the “arm’s length standard,” which was coined from the idea that related parties must price their transactions as if they were dealing at “arm’s length,” meaning as independent parties would in comparable circumstances.

Born from this legislation, the arm’s length principle states that transactions between related parties must be priced as if they were between independent, unrelated parties operating under comparable circumstances.

Still on the Indian subsidiary example, the arm’s length principle simply asks: If you weren’t dealing with your own subsidiary; if you were negotiating with a completely independent company, what price would you agree to?

Internationally, the principle gained universal acceptance through Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention, which established the arm’s length standard as the international norm. The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, first published in 1995 and regularly updated, provide the detailed framework that over 100 countries now follow.

Today, transfer pricing laws exist in nearly every major economy, including the UK, India, Germany, Canada, Australia, China, and dozens more, all built on this same foundation.

Types of Transfer Pricing

When you need to establish arm’s length pricing for transactions between your related entities, you can’t just pick a number out of thin air. Tax authorities require you to use recognized transfer pricing methods. These are systematic approaches to determine what independent parties would charge in comparable situations.

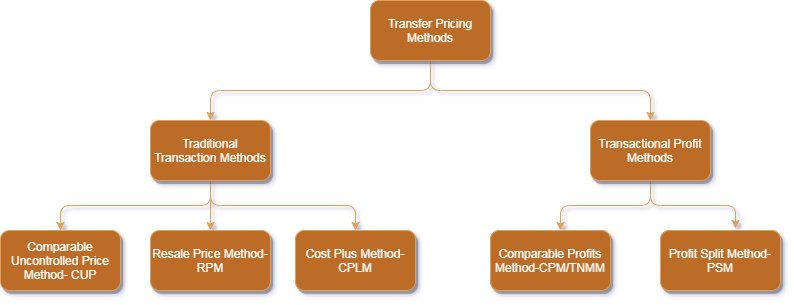

These methods fall into two main categories: traditional transaction methods and transactional profit methods. Let’s break them down.

Traditional Transaction Methods

These methods directly compare the price or gross margin in your intercompany transaction to prices or margins in comparable uncontrolled (independent) transactions. They’re considered the most direct way to apply the arm’s length principle.

1. Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) Method

The CUP method compares the price charged in your intercompany transaction to the price charged in comparable transactions between independent parties. This is the most straightforward application of the arm’s length principle. If you can find what independent parties charge for the same or similar goods or services under similar circumstances, that’s your benchmark.

Still using the same narrative, if your US parent company pays your Indian subsidiary $500,000 annually for software development services. To apply CUP, you discover that you also hired an independent Indian dev shop last year for a similar project and paid them $850,000 for comparable work. This internal comparison suggests your arm’s length price should be closer to $850,000, not $500,000.

CUP comes in two forms: internal (comparing your intercompany price to prices you charge independent parties) and external (comparing to transactions between other independent parties). If differences exist between the transactions, adjustments must be made to account for them. This method is preferred when reliable comparables exist, but finding truly comparable transactions is often the biggest challenge.

2. Resale Price Method (RPM)

The Resale Price Method starts with the price at which your subsidiary resells a product to independent customers, then subtracts an appropriate gross margin to arrive at the arm’s length transfer price.

The logic is simple: if your subsidiary buys from your parent and resells to customers, the gross margin they earn should be comparable to what independent distributors earn for similar functions. The formula is: Transfer Price = Resale Price – (Resale Price × Resale Margin).

Let’s say your US company manufactures a hardware device for $80 per unit and transfers it to your European subsidiary, which resells to customers for $200 per unit. If comparative analysis shows that independent distributors in similar European markets earn gross margins of 35-40% for comparable products and functions.

Calculating the transfer price at both ends of the range:

- At 35% margin: Transfer Price = $200 – ($200 × 0.35) = $200 – $70 = $130 per unit

- At 40% margin: Transfer Price = $200 – ($200 × 0.40) = $200 – $80 = $120 per unit

This means your arm’s length transfer price should fall between $120 and $130 per unit to be at arm’s length.

This method works best when your subsidiary acts primarily as a distributor or reseller without substantially transforming the product or adding significant value. The key is finding comparable gross margins earned by independent distributors performing similar functions, bearing similar risks, and using similar assets.

3. Cost Plus Method (CPM)

The Cost Plus Method calculates the transfer price by taking the supplier’s costs and adding an appropriate markup that independent companies would earn for similar functions. This method is commonly used for services, manufacturing, and other situations where one entity incurs costs to provide something to a related entity. The formula is straightforward: Transfer Price = Costs + (Costs × Markup Percentage).

In this scenario, your Indian subsidiary provides software development services to your US parent company. First, you calculate the subsidiary’s total annual costs: engineer salaries, office infrastructure, and overhead come to $500,000. Next, through benchmarking research using industry databases, you find that independent Indian software development firms performing similar services earn markups ranging from 20-30% on their costs.

Calculating the transfer price at both ends of the range:

- At 20% markup: Transfer Price = $500,000 + ($500,000 × 0.20) = $500,000 + $100,000 = $600,000

- At 30% markup: Transfer Price = $500,000 + ($500,000 × 0.30) = $500,000 + $150,000 = $650,000

This means your US parent should pay between $600,000 and $650,000 annually for the development services.

The critical elements are determining which costs to include (direct costs only, or also allocated overhead?) and finding comparable markups. You need to identify independent companies performing similar functions with similar cost structures, then determine what markup they earn on their costs.

Transactional Profit Methods

These methods examine the profits arising from particular transactions between related parties. They’re often used when traditional methods aren’t reliable due to a lack of comparable transaction data or when dealing with complex value chains.

4. Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM)

TNMM compares the net profit margin (relative to costs, sales, or assets) that your entity earns from intercompany transactions to the net margins earned by independent companies performing similar functions. Unlike the traditional methods that look at prices or gross margins, TNMM examines operating profit. You identify the entity performing simpler, more routine functions (the “tested party”), calculate a profit level indicator (PLI) such as operating margin on costs, and compare this to PLIs of comparable independent companies.

This is the most widely used transfer pricing method globally because it’s flexible and doesn’t require finding comparable transactions; you only need comparable companies, which are easier to identify through database searches. Common PLIs include operating margin, return on costs, and return on assets.

5. Profit Split Method (PSM)

The Profit Split Method divides the combined profits from intercompany transactions between related entities based on their relative contributions of functions, assets, and risks. This method is used when multiple entities make significant, unique, and interrelated contributions that cannot easily be evaluated separately. Rather than testing one party against independent comparables, you analyze how independent parties would have divided profits if they had made similar contributions.

There are two main approaches: contribution analysis (splitting profits based on relative value contributions, often measured by costs, headcount, or assets) and residual analysis (first allocating routine returns to each entity, then splitting remaining profit based on non-routine contributions).

The method requires detailed functional analysis and often involves subjective judgments about value creation, making it the most complex method, but sometimes the only appropriate one for highly integrated operations or unique intangibles developed jointly.

Transfer pricing disputes arise when tax authorities believe your prices don’t align with market rates or that you’ve applied the wrong method. These disputes can result in profit adjustments, additional tax obligations, penalties, and the nightmare of double taxation across multiple jurisdictions. Choosing the method that best reflects what independent enterprises would do helps you avoid audits and pricing adjustments before they happen.

When Do You Have to Start Worrying About Transfer Pricing

The short answer: the moment you have related entities transacting across borders.

Many founders assume transfer pricing is something to worry about “later”—maybe after Series B, or when they’re doing tens of millions in revenue, or when they’re closer to an exit. This is an expensive misconception. Transfer pricing isn’t triggered by your company’s size or revenue. It’s triggered by your corporate structure.

The Immediate Triggers

You need to think about transfer pricing as soon as any of these happen:

You set up a foreign subsidiary or branch. The second your Indian subsidiary invoices your US parent (or vice versa), you’re making transfer pricing decisions—whether you realize it or not. There’s no grace period, no “we’re too small” exemption, no waiting until you’re profitable.

You hire employees or contractors through an overseas entity. If your German subsidiary employs developers who work on your product, and your US entity benefits from that work, there’s a transaction happening. How much should the US entity pay the German entity? That’s transfer pricing.

You license IP across borders. Your Delaware C-corp owns your patents and trademarks. Your UK entity uses them to sell to European customers. What royalty rate should the UK entity pay? Transfer pricing question.

You establish shared service arrangements. Your US headquarters provides HR, finance, and IT support to your Singapore entity. Do you charge for these services? How much? Transfer pricing.

You transfer goods between entities. Your manufacturing subsidiary in Vietnam ships products to your US distribution entity. At what price? Transfer pricing.

The “Too Small” Myth

You may be thinking, “We’re just a $2 million ARR startup. Tax authorities don’t care about us.” The truth is, in the United States, there’s no specific dollar threshold that triggers mandatory transfer pricing documentation.

Under Section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code, the IRS has the authority to adjust income and deductions between related parties to prevent tax evasion and clearly reflect income, regardless of company size. You’re technically required to use arm’s length pricing from day one. The difference is penalty protection—without proper documentation, you’re exposed to penalties if the IRS audits you and makes adjustments, even on relatively small amounts.

More importantly, transfer pricing issues compound over time. That casual decision you made in 2024 about how to structure payments to your Indian team? Tax authorities can audit back 3-7 years (longer in some jurisdictions). By the time they come knocking in 2028, you’ll have four years of potentially “wrong” pricing to explain, with penalties and interest if they are correct.

Start worrying about transfer pricing the moment you create your first cross-border related-party transaction. Not when you’re big enough, not when you’re profitable enough, not when it’s convenient. If you have more questions about the process of the IRS, you can check their transfer pricing FAQs (about everything ranging from best method review panel to country-by-country reporting, and international compliance assurance programs) to find answers.

Wrap Up

Transfer pricing sounds like something only EY partners whisper about in boardrooms of Fortune 500 companies. But if you’re a founder building anything with a global footprint—remote teams, overseas subsidiaries, international customers, cross-border IP—this is your problem now. And unlike most tax issues you can fix during cleanup before an exit, transfer pricing mistakes compound over the years and are brutally expensive to unwind.

FAQs

What’s the Difference Between Transfer Pricing and a Transfer Pricing Study?

Transfer pricing refers to the actual prices you charge for transactions between your related entities across borders. A transfer pricing study is the formal documentation that proves those prices comply with the arm’s length principle, including functional analysis, economic benchmarking, and your pricing methodology. Think of it this way: transfer pricing is what you do; the transfer pricing study is how you prove it’s compliant.

Do I Need to Worry About This if My Startup Is Still Small?

Yes, if you have cross-border transactions between related entities. In the US, Section 482 requires arm’s length pricing from day one with no minimum threshold, and without proper documentation you’re exposed to 20-40% penalties if audited. Many other countries have explicit requirements kicking in at $1-2 million in related-party transactions. Tax authorities can look back 3-7 years, so decisions made today become expensive problems later.

What Happens if Tax Authorities Disagree With My Transfer Pricing?

They can reallocate income between your entities, resulting in additional tax liability, penalties of 20-40% without adequate documentation, interest from the original tax year, potential double taxation, and possible audit expansion to other years. You can challenge adjustments through appeals or litigation, but it’s expensive—better to get it right upfront.

What Records Should I Keep?

Keep intercompany agreements, pricing rationale with benchmarking data, functional analysis of each entity, financial records including invoices, documentation of business changes, and management decisions. Maintain these for the statute of limitations period (typically 3-7 years). “Contemporaneous” means created when decisions were made, not after an audit begins.

Can I Use Different Transfer Pricing Methods for Different Transactions?

Yes. Different transactions may warrant different methods—Cost Plus for development services, TNMM for sales operations, CUP for IP licensing if you license to independents. Select the most appropriate method for each transaction based on facts and available data, then document your rationale. You cannot method-shop to minimize taxes—you must use the most reliable arm’s length approach.